Before joining DWP, had you ever been scuba diving?

I was not familiar with scuba diving in the slightest! But I grew up in Miami, Florida, by the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. I have a lot of memories of going to Crandon Park, which is a historically African American beach, and snorkeling with my mother and my grandmother. It wasn’t until a colleague came back from his first dive with DWP that I became interested. His eyes were so wide with excitement that I was like, “All right, let me see . . .”

What was your first dive like?

It changed my entire life. It was in St. Croix. I saw everything from huge purple sea fans to ship anchors stuck into coral reefs. It was a beautiful experience to see the vibrancy of the sea life and also to feel the vastness of the ocean around me.

How does DWP find the shipwrecks?

We often partner with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It oversees several hundred wreck sites but doesn’t have enough staff to document all of them. A NOAA archaeologist usually gives us the historical background of a particular site, as well as its GPS coordinates so we can find it.

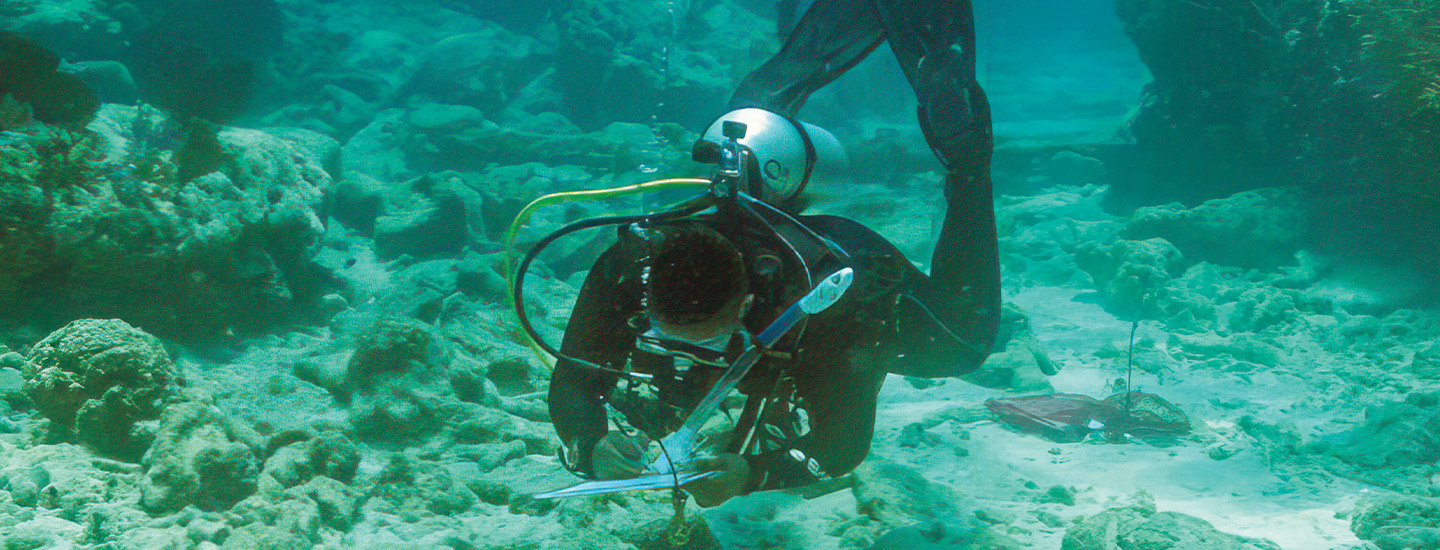

What happens during a dive?

The lead divers lay a line of measuring tape from one end of a wreck site to the other end. We use that line to divide the site. Then a pair of divers is assigned to each section. We take measurements of everything in our area.

When I first began, we used tape measures. But recently, to speed up the process, we’ve been diving with underwater GoPro cameras (see “Tools of the Trade,” below). We take thousands of images of each section. Later, computer software puts together the images, like puzzle pieces. This creates a detailed map of the entire wreck site. On a typical project, we spend two days getting the background information, three or four days in the water, and then a day afterward mapping.

What kinds of objects have you come across?

Fragments of plates, glass beads that were used for trading, metal pieces, and of course the ships, which are themselves artifacts. In 2021, we did a dive to an 18th-century wooden schooner, one of the oldest ships recovered in the waters near St. John. We found a glass bottle that was likely produced in the mid-18th century; we know that because of the shape of the bottle. Those kinds of artifacts are really exciting because they help give you a date for the wreck itself.